What is a contract manufacturer?

The current administration’s newly announced additional tariffs on goods coming from China, one of our strongest trade partners, has led to economists sounding the warning bells that it could lead to higher prices in the US on everything from iPhones to avocados — two things Americans can’t get enough of.

But let’s remind ourselves of the basics: Tariffs are a tax collected by the government and paid for by the businesses bringing goods into the country. Businesses then increase their prices for consumers to make up for the cost of the tariffs. Before we spiral too far down the path of “more things should be manufactured domestically,” it might be helpful to look at what role a contract manufacturer (CM) plays and understand why exactly they’re so much more successful in China than the US.

What the inside of most CMs look like.

Most consumer electronics are manufactured using a CM, who take all the components of a product (the ingredients) and assemble them in a repeatable manner (the recipe). You can think of your bill of materials (BOM) as your ingredients list: cables, batteries, circuit boards, plastic parts, etc; and your assembly/work instructions are the steps of your recipe. As a product designer or engineer, it’s your job to help create the recipe and the ingredients list, and it’s the CM’s job to consistently make the parts according to your instructions. It’s important to work with your CM through the “design for manufacturing” phase of work to reduce avoidable errors and expenses. We’ve talked about this at length here and here.

Your BOM is made up of many parts at varying volume requirements and from different vendors. A CM serves as the central hub, pricing and procuring all of these individual parts from their network of trusted vendors. For each one of these parts, the CM negotiates pricing based on both your manufacturing volumes and the greater extent of their business with that vendor. They often get much better pricing from a supplier than if you were to reach out on your own. For more complicated components, like gearboxes, wire harnesses, or subassemblies, the CM also typically manages the relationship with subvendors. For example, to source a wire harness, a CM could be dealing with four different vendors, one for the harnesses, one for the connectors, one for the housings, and one for the wires. They manage this giant spider web and ensure parts arrive correctly and on time.

CMs tend to handle the fabrication of circuit boards in house, and leverage partners for making things like test fixtures. They also have equipment and teams to perform incoming part inspections and lifetime testing of the final assembled units. They hire and train skilled assembly workers and often provide food and board as well.

Can CMs in the US make our products affordably?

In a nutshell, the answer is no, and it comes down to three main factors: proximity, experience, and culture.

Over the years, China (specifically Shenzhen or Dongguan) has built up an incredibly rich network of trusted suppliers — all centrally located — which is something we simply don’t have in the States. Not only are there many CMs all in the same city, but each one has a reputation for specializing in a specific category or product type. There are also thousands of local subsuppliers for incredibly cheap noncritical components (such as resistors and fasteners) that just don’t exist in the US.

The US doesn’t have a central manufacturing city filled with a rich local supplier network with the expertise required to manufacture a myriad of consumer electronics products at scale. Sure, you might have a cable vendor in Detroit, but your plastics supplier might be in Dallas. Everything is scattered across the US, and requires costly shipping fees to get it to a central hub for assembly. Manufacturing domestically requires logistics coordination across multiple time zones, third-party vendors managing shipments, and then when something gets lost or delayed or doesn’t pass QC, how are you going to address that complicated mess? Bottom line: We don’t have a central network of suppliers, vendors, or CMs with the expertise — let alone cultural norms — that would make assembly work cost-effective.

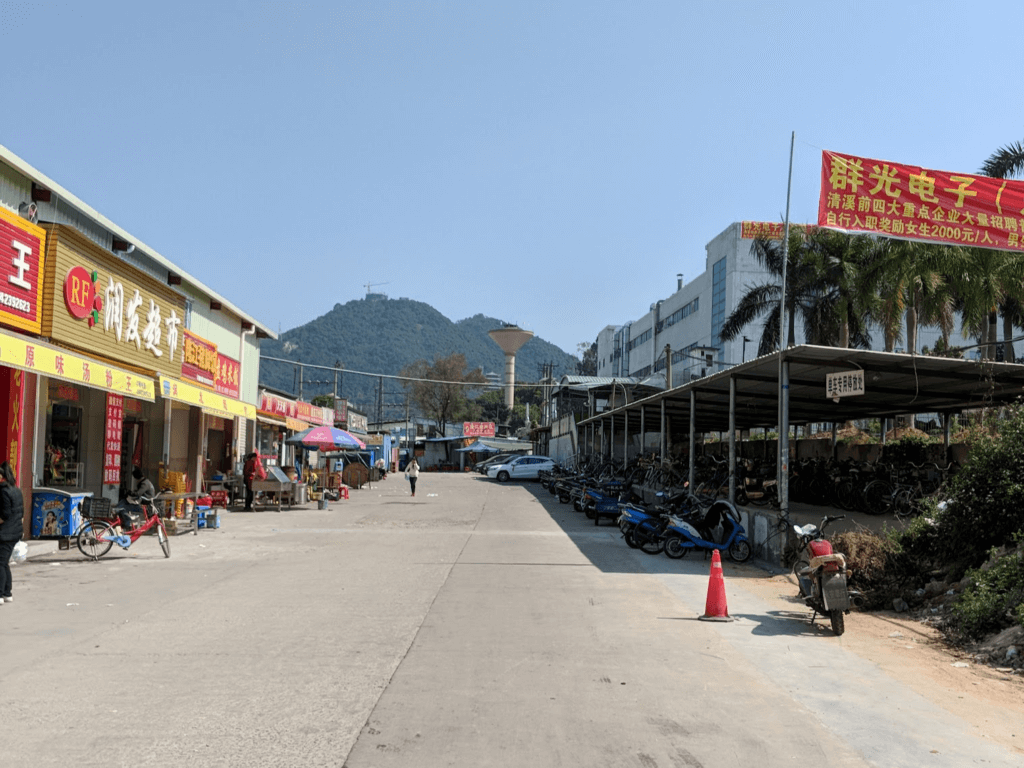

CMs tend to be located in Dongguan and Shenzhen. Outside of the CM, you can find small towns to support to local workforce.

We do have a few very specific instances of domestic manufacturing working well, but they’re specialized in fields like telecommunications, biomedical, aviation, and automotive. The things that make sense to manufacture domestically are items that are large in scale/size, small in quantity, high in price and with high margins, or can’t be outsourced. Think refrigerators, or even more complicated are telecommunications equipment that live at the base of a telephone pole. That’s what we excel at in the US. We don’t have enough people who make high-volume, high-quantity, high-quality parts that are low cost. And for the ones that exist, they’re simply not connected well to each other.

And of course we can’t forget cost of production. Wages in the US are significantly higher than wages in China, which is great! However, we lack a trained workforce for factory work. Environmental and labor policies are stricter here as well (though the current administration is working to erode those laws). Having protections for workers and the planet is good for us as a society, but it also makes it tough for us to do this kind of production work at scale.

Then there’s the overall cost to own a facility, get electricity, hire locally, etc. The costs to manufacture in the US would increase prices significantly beyond the 10% tariffs on Chinese manufactured products. At the end of the day, many of the parts would still need to be supplied by Chinese manufacturers.

For all of these reasons, burgeoning companies in the US simply can’t afford to manufacture in the US without massive increases in the costs, which the customers would need to pay. Many startups also are manufacturing at lower scales that risk-adverse US-based CMs tend to avoid. China operates on volume, and due to our lack of scale, we don’t have the capacity or demand to compete. It’s just a different dynamic and an engine for scale built over decades. A 10% tariff isn’t ideal, but for most startups, China is still more cost effective by far than the alternative.

informal is a freelance collective for the most talented independent professionals in hardware and hardtech. Whether you’re looking for a single contractor, a full-time employee, or an entire team of professionals to work on everything from product development to go-to-market, informal has the perfect collection of people for the job.